No Fault Divorce Impact on Divorce Statistics Families

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

Do changes in divorce legislation take an impact on divorce rates? The case of unilateral divorce in Mexico

Latin American Economic Review volume 28, Article number:9 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

In 2008, Mexico Urban center was the first entity to corroborate unilateral divorce in United mexican states. Since then, 17 states out of 31 have also moved to eliminate fault-based divorce. In this paper, I investigate the effect of the changes in unilateral legislation on divorce rates in Mexico, given the remarkable growth of divorce rates over the by few decades in the land, but specially later on the introduction of unilateral divorce. Following a difference-in-differences methodology, two models are developed using panel country-level information. The results betoken that divorce on no grounds accounts for a 26.four% increase in the total number of divorces in the adopting states during the period 2009–2015. Moreover, since no-mistake divorce has been implemented gradually in the land, the rising trend in divorce rates is expected to continue over the coming years. Unilateral legislation has proved to exist an constructive tool in modifying family structures in Mexico, so it is important to exist aware of the short- and medium-term consequences of the shift toward divorce on no grounds, in order to improve the delivery of these policies in the country. This is especially important at this signal in time, when 14 remaining states may potentially prefer unilateral legislation. This paper is the first one to accost the effect of adopting unilateral divorce in the context of a Latin American country.

Introduction

Divorce has legally existed in Mexico for over a century. In contrast to other countries such as Italy, Brazil, Spain, Argentina, Ireland or Chile, where divorce was forbidden until 1971, 1977, 1981, 1987, 1997 and 2004, respectively, the Mexican legislation has immune for divorce since 1914. Notwithstanding, to file for divorce, a mutual understanding between the spouses had to exist; otherwise, a contested divorce (where the parties exercise not agree and demand to fight it out in court) still had to take place. Therefore, compared to Commonwealth of australia or the USA, where unilateral divorce (a divorce in which one spouse ends the marriage without the consent of the other spouse) has been pop since the early 1970s, the country has lagged behind.

Divorce rates in Mexico have exhibited an upward trend in the past decades, but later on the introduction of unilateral divorce in some entities, this tendency has grown remarkably. Therefore, the objective of this written report is to analyze whether divorce rates respond to the implementation of unilateral divorce within the context of a developing country, in this case, Mexico.

Mexico comprises 32 entities, 31 states and Mexico City. Each one of them regulates its citizens independently through their own constitutions, civil codes and penal codes, among others, which are the counterparts to the comprehensive federal regulatory structure. All petitions for divorce are handled by entity courts. In Oct 2008, Mexico City was the first entity to approve unilateral divorce, and since then, 17 states have also moved to eliminate fault-based divorce. Information technology took 7 years, between 2008 and 2015, for these changes to happen in 12 entities, only in just i year, 2016, six more immune no-fault divorce. Footnote 1 A possible caption for the increasing number of states that take recently modified their legislations in terms of divorce is that in July 2015, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation determined that information technology is unconstitutional for states not to permit a spouse to end a marriage unilaterally, without the need to provide a cause to deliquesce the matrimony. Footnote 2 However, the Supreme Courtroom resolution regarding unilateral divorce does not make whatsoever state law invalid, since information technology is only a jurisprudential thesis. Footnote iii From a legal perspective, unilateral divorce is therefore settled in the country, but there is an implementation problem that causes longer and strenuous divorce processes in those states that accept non yet adopted divorce on no grounds. Table ane shows the entities that have modified their local laws to adopt no-fault divorce, the year when the reform was introduced, and information most the legislation that validates unilateral divorce in the state. Footnote 4

The economical literature suggests that state interventions to correct externalities are non necessary when property laws are clear and transaction costs are low because the parties will get together and negotiate a individual agreement until they achieve an efficient solution. Based on this assumption, efficient bargaining has been extended to marriage decisions, and the merits is that if the spouse who wishes to leave the union tin bargain at a depression price with the spouse who wishes to stay, the only factor that matters for the dissolution of the union is the bounty negotiated, regardless of the allocation of holding rights or legal liability (Becker et al. 1977). The statement is further elaborated in Becker (1991, p. 331): "A husband and wife would both consent to a divorce if, and only if, they both expected to be better off divorced. Although divorce might seem more difficult when mutual consent is required than when either alone can divorce at volition, the frequency and incidence of divorce should be similar with these and other rules if couples contemplating divorce can easily deal with each other. This exclamation is a special instance of the Coase theorem (1960) and is a natural extension of the statement (…) that persons marry each other if, and only if, they both expect to be better off compared to their best alternatives." The theoretical justification provided by Becker (1991) framed in terms of Coase'southward (1960) theorem leads to the decision that only inefficient marriages would disolve and efficient divorces would occur, regardless of the legal organization. Therefore, modifications in divorce legislation should have no effect on the total number of divorces, and the adoption of a no-fault divorce regime should have no effect on divorce rates.

However, critics of Becker'southward proposition take emerged. Even if there were perfect information and no transactional costs, it has been argued that divorce laws would affect divorce decisions because of the importance of assets and resource allotment before and after the divorce, along with divorce legislation, for determining the gains and losses from dissolution and for influencing the determination to end the matrimony (Clark 1999). In addition, if Coase's theorem every bit applied to matrimony contracts were discarded, it has been claimed that to assume that divorce rates are not influenced by divorce legislation considering the gains from marriage are not affected by more liberal divorce laws would be to deny that the easier it is to get a divorce, the lower is the value of marital surplus due to more attractive outside options (Mechoulan 2005).

In an effort to reconsider the theoretical validity of the then-called Becker–Coase theorem, inside the context of households that consume public as well every bit individual goods, information technology has been found that as a general rule, reforms in divorce legislation are expected to affect divorce rates, just the effect tin can be either positive or negative, co-ordinate to the situation of each couple. Moreover, this opens up the possibility that the Becker–Coase theorem can nevertheless concord, every bit long as the consumption of the public goods involved in the marriage is not altered after the divorce (Chiappori et al. 2015).

Sometimes changes in public policies have unintended effects on people's lives and their relationships with others. Even though no-error divorce legislation was originally intended as a solution for inherent disputes in a error-based divorce regime, enquiry in different countries has demonstrated that unilateral divorce laws have acquired an increase in the full number of divorces than would have occurred otherwise.

The discussion regarding the impact of unilateral divorce has turned into a battlefield in the public sphere. While some merits that it is a less adversarial divorce organisation, which respects the privacy of the marriage since no evidence against either of the spouses is needed, others fence that unilateral divorce laws undermine the institution of marriage, encouraging marital irresponsibility and taking away bargaining leverage from the political party who is neither at fault nor desirous of a breach, since the processes of determining belongings distribution, alimony and child custody are separated from the divorce trial.

To add to the debate on the effects of unilateral divorce, information technology has been argued that social changes after the Second World War led to a ascension in the number of inefficient marriages and that no-fault legislation contributed to transforming previously inefficient marriages into efficient divorces but also to converting efficient marriages into inefficient divorces (Allen 1998). Furthermore, it has been suggested that during the menses from 1965 to 1996, the adoption of unilateral divorce law in the Usa caused an increase in trigger-happy crime rates of approximately ix%. In the years following the reform, it was observed that mothers in adopting states were more probable to become the caput of the household and to autumn below the poverty line, especially less educated mothers. A potential link between the unilateral reform and the increase in crime might have been worsening in the economic conditions of mothers and the increment in income inequality as unintended consequences of the reform (Caceres-Delpiano and Giolito 2012). Empirical evidence also shows that adults who were exposed to unilateral divorces every bit children have lower family incomes, are less educated and split up more often (Gruber 2004). On the other hand, making divorce easier decreases domestic violence for both men and women, reduces female suicide, lowers the number of females murdered past intimates and has a positive upshot on marriage investments such equally female labor strength participation (Stevenson and Wolfers 2006; Stevenson 2007).

Research on no-mistake divorce indicates both positive and negative effects when legislation is modified to allow for unilateral divorce, depending on the detail subject nether analysis. From a policy perspective, changes in divorce legislation might play an fifty-fifty more of import function in Mexico than in developed countries, strengthening women'due south bargaining position in the household, where women frequently lack the authority to brand key decisions. For instance, in terms of gender violence, information for United mexican states show that effectually 45% of women who have been in a relationship between 2006 and 2022 have experienced intimate partner violence. Footnote 5 Unilateral divorce non merely represents an option for abused wives to escape their marriages, but it also contributes to reducing domestic violence because husbands are less likely to abuse given a more than apparent threat to leave the marriage. Women in developing countries are also more than economically dependent. Mexican female person labor market participation is beneath the boilerplate for OECD countries with the 2nd everyman charge per unit just after Turkey (OECD 2017). As a result, the potential costs of divorce that Mexican married women bear can be unduly college relative to men. Divorce on no grounds reduces the time spent on accusations and legal fees, helping women cope meliorate with the fiscal divorce burdens and increasing their chances to end a bad union.

In this newspaper, to analyze the unilateral divorce effect on divorce rates in Mexico, a difference-in-differences (DD) assay is conducted using aggregate divorce data at the land level post-obit the methodology proposed past Wolfers (2006) and Friedberg (1998). In each year, the states that accept adopted unilateral divorce are considered the treatment grouping, while the states that remain under the error-based legislation are considered the command group. The DD technique has been used widely to written report numerous policy questions, and it is considered a pop tool for applied research in economics.

The results indicate that the shift toward divorce on no grounds raises the divorce charge per unit by 0.30 annual divorces per thousand people and accounts for a 26.4% increase in the total number of divorces in united states of america that modified their legislation during the period 2009–2015. To the all-time of my cognition, this is the offset study to analyze the bear on of unilateral legislation on divorce rates in a Latin American land, and it aims to contribute to a better understanding of divorce outcomes in the region, equally well equally the implications of these types of polices in developing countries.

The rest of the paper is outlined as follows: Section ii introduces the relevant literature; Sect. 3 discusses the estimation strategy; Sect. 4 presents the data; Sect. v shows the results for the static and dynamic specifications, as well every bit the results for alternative empirical approaches that are followed; and Sect. 6 presents the conclusions.

Literature review

Over the terminal 30 years, economists have devoted considerable empirical efforts to notice out whether liberalization in divorce laws is responsible for the rise in marital dissolution. Initially, unilateral legislation was found not to have an effect on the probability that a woman becomes divorced in the U.s. (Peters 1986), supporting the validity of the Becker–Coase theorem. Nevertheless, in an open criticism of this work, information technology was argued that the findings are incorrect, mainly due to the misclassification of no-fault and mistake states and the inclusion of regional dummies and that one time the methodological issues are corrected, the results testify that the shift from error to no-fault divorce regime indeed increases divorce rates (Allen 1992).

As an culling to deal with the lack of robustness of previous inquiry, using a panel of state-level divorce rates for the The states, a divergence-in-differences methodology is followed to identify the result of unilateral divorce on divorce rates (Friedberg 1998). The main business organisation to address is endogeneity, given the before adoption of unilateral legislation in states with higher divorce rates. Estimations are performed using the number of divorces that occur within a country each yr as the dependent variable divided past the country population in thousands. For the main independent variable, a dichotomous variable is created, which takes the value of 1 if the state had adopted unilateral legislation in that year and zero otherwise. State effects, twelvemonth effects and land-specific linear and quadratic fourth dimension trends are included as controls. The findings show non simply that states with legislation toward unilateral divorce have higher divorces rates but that during the flow from 1968 to 1988, unilateral divorce also accounted for 17% of the rise in divorce rates, suggesting a more permanent rather than temporal effect.

In order to reassess whether the short-run and long-run implications of the shifts in divorce regimes are different, previous inquiry was expanded to incorporate the dynamics of divorce responses (Wolfers 2006). The argument for the extension of the analysis is based on the notion that state-specific trends might be capturing non just preexisting trends but also the dynamic effects of the change in the legislation, misreckoning the two of them. To address this possibility, similar regressions to Friedberg's are estimated, only the sample menstruation is modified to 1956–1988 and 8 dichotomous variables are created to point whether the adoption of unilateral legislation had been in identify for at least ii years, 3–4 years, v–6 years, 7–8 years, ix–ten years, 11–12 years, thirteen–xiv years or 15 years or more. The results indicate that a alter in divorce legislation leads to a temporary increase in divorce rates merely that in that location is no evidence to suggest that this rise is permanent, showing that after a decade, the rise is reversed.

Similar inquiry has been carried out to analyze the issue of changes in divorce legislation on divorce rates in Europe. Pooling data together from 18 countries (Republic of austria, Kingdom of belgium, Denmark, Finland, French republic, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the Uk), the evidence supports previous findings that modifications in divorce law increase divorce rates, with strong long-term effects (Gonzalez and Viitanen 2009).

Furthermore, following an interactive fixed-effects approach, for a given number of factors (Kim and Oka 2014), and for an unknown number of factors (Moon and Weidner 2015), a curt-term issue on divorce rates due to unilateral legislation in the United states has also been found. The purpose of using an interactive fixed-effects model in this context is to command for unobserved heterogeneity across states (family size, religious beliefs and female labor force participation) that might evolve over time in a complex style, leading to mixed empirical evidence. Wolfers' specifications are followed, but the random error is assumed to consist of unobserved common shocks and an idiosyncratic error. Estimations are performed post-obit Bai (2009) and the least squares (LS) computer, respectively. It is important to highlight that the interactive fixed-furnishings methodologies used within this context are only valid for console data with big cross-sectional units (Due north) and large time periods (T). Footnote 6 Their potential implementation therefore relies on the specific characteristics of the datasets available. In this case, the panel data consist of 48 states over 33 years. Footnote 7

For developing countries, and more precisely for Latin American countries, scholarly economical inquiry on the effects of unilateral legislation on divorce rates is scarce. This is non surprising, every bit no-fault divorce has been in place simply for a few years in some of these countries, and at that place is limited quantitative data available to analyze its consequences for the structure of families. It is expected that this paper will stimulate interest in monitoring, reporting and evaluating the effects of these changes in the policies in the region and that more than research volition have place to better empathize the office that they play, given their specific cultural context.

Interpretation strategy

To analyze whether divorce rates in Mexico are responding to the implementation of no-error divorce, initially, the difference-in-differences interpretation arroyo used by Friedberg (1998) is followed:

$$\brainstorm{aligned} {\text{Divorce Rate}}_{s,t} = & \beta {\text{Unilateral}}_{southward,t} + \mathop \sum \limits_{south} {\text{Country fixed effects}}_{s} \\ & + \mathop \sum \limits_{y} {\text{Year fixed effects}}_{y} + \mathop \sum \limits_{s} {\text{State}}_{south} *{\text{Time}}_{t} \\ & + \mathop \sum \limits_{southward} {\text{Country}}_{southward} *{\text{Time}}_{t}^{2} + \varepsilon_{s,t} \\ \cease{aligned}$$

(1)

where \({\text{Divorce Rate}}\) is the total of divorces per thousand people Footnote eight and \({\text{Unilateral}}\) is a binary indicator for divorce legislation (unilateral = i). State-fixed effects are included to control for heterogeneity within states. Year-fixed effects account for changes in divorce patterns at a national level. Linear and quadratic country-specific time trends capture changes within states \(\left( s \right)\) over time \(\left( t \right)\).

In contrast to other papers where an important issue is the nomenclature of state divorce laws, which has the potential to reach different conclusions depending on the definition used, in the Mexican case this is not a problem. Although no-fault divorce and unilateral divorce represent to unlike situations, co-ordinate to the reforms adopted in Mexico, each state that has eliminated grounds for divorce has simultaneously incorporated unilateral divorce in its legislation.

Every bit mentioned in the previous section, Friedberg'south methodology poses the latent risk of confounding preexisting trends with the full adjustment of divorce rates after the change in legislation. To rule out this possibility, Eq. (1) is modified to capture the dynamic response of the policy reform and Eq. (two) is likewise estimated. Information technology is worth emphasizing that this should not be seen equally a mere extension or a robustness check only equally a ameliorate specification to control for the dynamics generated in the marriage market. The results obtained will help determine if the introduction of unilateral divorce has had a more temporal rather than a permanent effect on divorce rates.

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Divorce Charge per unit}}_{south,t} = & \mathop \sum \limits_{thou \ge 1} \beta_{m} {\text{Unilateral divorce has been in consequence for}} \,chiliad\, {\text{periods}}_{southward,t} \\ & + \mathop \sum \limits_{due south} {\text{Land fixed furnishings}}_{s} + \mathop \sum \limits_{y} {\text{Yr fixed effects}}_{y} \\ & + \mathop \sum \limits_{s} {\text{Country}}_{s} *{\text{Time}}_{t} + \mathop \sum \limits_{s} {\text{State}}_{s} *{\text{Time}}_{t}^{2} + \varepsilon_{s,t} \\ \end{aligned}$$

(2)

The binary indicator for divorce legislation in Eq. (ane) is substituted by three dummy variables that indicate if unilateral divorce has been effective for 1 to ii years, iii to 4 years and five years or more. The inclusion of these variables allows united states to identify to what extent the increase in divorce rates is afflicted by modifications in divorce legislation (Wolfers 2006).

Heterogeneity across states and fourth dimension exists and may affect divorce rates and divorce legislation. The inclusion of factors such as unemployment and fertility rates in the standard approach allows for estimating the parameters more precisely (Gonzalez and Viitanen 2009). Equations (1) and (ii) are thus re-estimated including the following set of controls: female labor force participation, unemployment, fertility rate, teaching and gross domestic production.

Since the divorce rate is the full of divorces per 1000 population, the error term represents the sum of all individual disturbances in a state \(\left( southward \right)\) at time \(\left( t \right)\), divided by the population, leading to heteroscedasticity. In gild to right standard errors and to gain efficiency, weighted least squares (WLS) using population is implemented to perform all estimations. Footnote 9

Data

The National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) provides data on all the divorce records registered in the country by year. For the purposes of this analysis, country-level panel data are used for a period of 10 years, from 2005 to 2015. Although Mexico Urban center was the first entity to adopt unilateral divorce in 2008, and since so 17 more states have changed their divorce legislation to divorce on no grounds, the sample is also extended back to 2001 and 1993, in order to accost potential preexisting state-specific trends, and to verify whether the master results are nevertheless valid.

Table 5 in Appendix shows the divorce rates past state for the period analyzed. For most of the states that accept shifted to unilateral legislation, a substantial ascent in the divorce rates is observed in the year when no-fault divorce is adopted or in the year afterwards, and no anticipation effect is identified prior to the change in law. Thus, for those states that modified their legislation in the second one-half of the year, the first year considered as affected by the reform is the side by side year. Footnote 10 Following this arroyo, and since divorce data are available up to 2015, at that place are ten treatment states included in the analysis: Aguascalientes, Coahuila, Mexico Metropolis, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Mexico, Nayarit, Quintana Roo, Sinaloa and Yucatan. Footnote eleven Table 5 does not indicate any systematic increase in divorce rates before the adoption of unilateral divorce, suggesting no endogenous legislation. It was verified whether a correlation exists between the initial divorce rates and the change in a state'southward divorce police force and between the initial divorce rates and the yr when the state adopted divorce on no grounds. The lack of significance of all the correlation coefficients reported in Table half dozen in Appendix suggests that information technology is unlikely that a contrary causality exists and that the shift toward no-error divorce is exogenous rather than caused by a preexisting ascent in divorce rates in the adopting states.

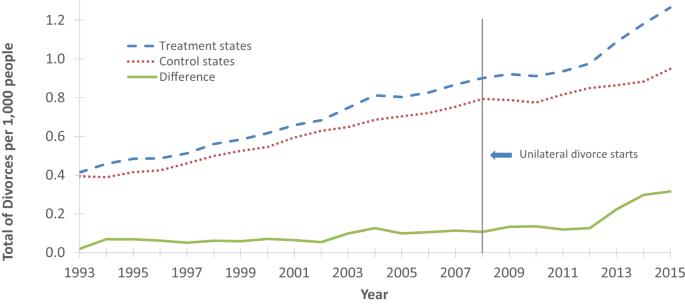

It is too relevant to ask to what extent the inclusion of land-level fixed effects in the model is justified in guild to control for different unobserved state-level factors affecting divorce rate trends. Figure 1 in Appendix illustrates the average divorce rate for the group of states that accept adopted no-error divorce (treatment states) and those who remain under the traditional divorce legislation (command states) for the menstruum 1993–2015. The difference observed between the average divorce rates for the treatment and control groups is close to zero during the first 10 years, just it starts to gradually increase afterward, providing show for differentiated trends and reaching a maximum of 0.32 in 2015. Similar average divorce rates, particularly before whatever state adopted no-mistake divorce, could be an early on indication that unobserved heterogeneity across states does not nowadays a threat of omitted variable bias, suggesting that state-level fixed effects might not play every bit much of a crucial role in Mexico as in other countries.

(Source: Writer's calculations. National Establish of Statistics and Geography (INEGI))

Average divorce rates

Data on the state population are needed to obtain the divorce rates. The National Population Quango (CONAPO) simply provides projected estimates for the period 2010 to 2015; therefore, the Mexican Labor Force Survey (ENOE) collected by INEGI is a more accurate source of these data, as well equally for female labor force participation and unemployment rates. Fertility rates and gross domestic product were also obtained from INEGI, and teaching data were obtained from the Secretariat of Public Teaching (SEP). Finally, the standing legislation in each country has been verified to fully place the states that accept legalized unilateral divorce versus those that are yet requiring grounds to grant divorce.

In contrast to the dataset used for the U.s.a., a potential limitation in the Mexican instance is the borderline small number of cantankerous-exclusive units (32 states) and time periods (10 years) available to conduct the analysis. It has been customary in deviation-in-differences empirical applications to overlook the possible consequences of the terms of statistical inference within this context, but a growing body of the literature acknowledges the demand for alternative techniques to properly account for problems such as serially correlated errors, cross-sectional dependence and heteroscedasticity (Donald and Lang 2007; Conley and Taber 2011; Ferman and Pinto 2018). There is no consensus on a straightforward approach to follow, and each method that has been established, such every bit cluster balance bootstrap, synthetic control computer, viable generalized least squares and 2-step estimators, among others, aims to bargain with specific circumstances. Moreover, as indicated earlier, there are ten states in Mexico that have shifted their legislation toward unilateral divorce in the dataset available (handling states); for two of them, however, Aguascalientes and Nayarit, the change only took place in the last year, 2015. This poses an boosted challenge for identifying the truthful outcome of the policy change, rather than its immediate effect. The development of a new inference method in the current Mexican setting is out of the scope of this paper, but the study takes a proactive approach and provides sensitivity analyses and robustness checks that aim to validate the main results obtained following the standard approach.

Results

The results are presented in the post-obit sections. Department 5.1 shows the estimations for the static specifications, while Sect. 5.ii presents the outcomes when the model is enhanced to properly capture the dynamic response of divorce rates. In Sect. 5.3, command variables are added to the static and dynamic models to account for observed heterogeneity, and in Sect. 5.four, alternative empirical approaches are followed to determine if the principal conclusions proceed to be valid.

Static specifications

Table 2 reports estimates of the static furnishings on divorce rates when unilateral legislation is adopted. The estimates suggest that unilateral divorce raises divorce rates in United mexican states. All coefficients of unilateral are statistically significant. The first specification in column (1) does not include fixed effects, and it is observed that its coefficient for unilateral is the largest. It captures non only the event of the modification in the divorce legislation but also other changes on divorce patterns over time and beyond states. To better the model, controlling for the average differences in states and years, specification (2) includes year and state effects. The coefficient indicates that the adoption of unilateral divorce raises the divorce rate past 0.32 almanac divorces per thousand people. While the year effects capture evolving unobserved characteristics at a land level, and the state effects command for constant factors over time that influence divorce decisions; specifications (3) and (4) represent more than flexible models where attributes that affect divorce propensities in each state are immune to alter over time. The results showroom a smaller effect of no-fault divorce when linear and quadratic state trends are included.

The F statistics for the state trends in columns (3) and (4) prove that the significance level of the examination equals nix, reflecting that state trends are jointly significant, both linear and quadratic. In add-on, moving across the columns, the adjusted R 2 increases from 0.89 in specification (2) to 0.95 in specification (4), supporting the inclusion of state trends every bit relevant to the model. A possible explanation for the pocket-size variation in the unilateral coefficient when land trends are added, compared to other countries such as the USA, might be the homogenous gender inequality that is predominant in all Mexican states to this 24-hour interval. Women'due south decision-making power within the household is limited in the country, and therefore simply an external shock such as an unexpected alter in the divorce legislation triggers a structural change in the marriage market, disrupting traditional gender roles and stereotypes. It may also be the example that the main factors that have an affect on divorce rates within states have not changed much over the flow analyzed. In Sect. v.three, the results are presented when some of these potential factors are explicitly included in the estimations. Every bit an only exception, in specification (4), the F test for the year effects fails to reject the cypher hypothesis that the coefficients for all years are jointly equal to zero, suggesting that there is no need to include twelvemonth-fixed furnishings in the model. Tabular array 7 in Appendix provides the estimations for all specifications excluding year effects. The impact of unilateral legislation on divorce rates remains positive, significant and similar in magnitude.

Because that Friedberg (1998) used specifications similar to those in Table 2 for the U.s. and obtained a variation betwixt 0.004 and 1.fourscore in annual divorces per m people due to unilateral legislation, it can be argued that in the case of Mexico, regardless of the model used, the static furnishings of unilateral legislation do non vary much beyond specifications, from 0.23 to 0.39. This suggests that the model is appropriate for the state and that there is a strong and steady relationship between changes in divorce law and divorce rates in Mexico. The unilateral coefficient in specification (three), for instance, represents 34.9% of the boilerplate divorce rate of 0.85 annual divorces per chiliad population for the period analyzed. Moreover, the adoption of unilateral legislation has increased the divorce charge per unit by 26.four% in the shifting states during the period 2009–2015.

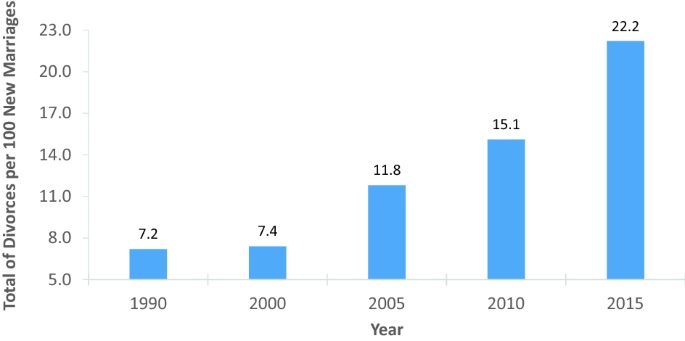

An issue for the robustness of the results presented above is the number of years considered in the analysis earlier the policy shock, to properly account for preexisting state trends. This is less of a problem for those states that take shifted to unilateral divorce more than recently but remains a controversy for those that started before, such as Mexico Urban center (2008) or Hidalgo (2011). Tabular array 3 reports the static furnishings on divorce rates for the menstruation 2001 to 2015. Comparing Tables 2 and 3, it is observed that the inclusion of boosted years pre-reform plays no major office in the analysis. Estimations for a larger period, from 1993 to 2015, are also provided in Table eight in Appendix, and the findings remain unchanged. It is to be noted that adding information where all states are untreated (1993 to 2004) tends to increase the unilateral coefficient. For instance, in Table 2, specification (four) indicates that no-fault legislation raises divorce rates by 0.23 annual divorces per thou people, whereas in Table 3, specification (iv) shows an increment in 0.29 annual divorces per g people. Opposite to what is observed, information technology is expected that adding data where all states are untreated would reduce the coefficient. This finding might reflect the almost null variation in divorce rates during the pre-reform years at the national level, reinforcing the effect of the change in the divorce legislation rather than diluting it when the data are extended back. According to data from INEGI, in 1990 and 2000, in that location were seven divorces for every 100 new marriages. By 2005, this rate rose to 11.8, and in 2015, it reached 22 per 100 new marriages (see Fig. 2 in Appendix).

(Source: National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI))

Divorces per 100 new marriages in Mexico

Dynamic specifications

The aim of this section is to examine the potential bias resulting from unmeasured confounders. As mentioned earlier, outcomes from Eq. (1) might be biased measures of the causal event of unilateral divorce on divorce rates considering the unilateral coefficient is not allowed to modify after the adoption of no-fault divorce, confounding preexisting trends with the dynamic effects of the policy daze. When a policy shock takes place, depending on the circumstances, the impact may be immediate or occur with considerable delay; it either has a permanent effect or dies out at a relatively fast pace. Wolfers (2006) analyzes the short-, medium- and long-run effects of the adoption of unilateral police in the United states. In the case of Mexico, the shift toward no-fault divorce is a recently enacted legislation, starting in 2008, so the analysis is focused on the brusque and medium term. Table 4 presents the furnishings that unilateral legislation has on divorce rates within the offset 2 years of the change in the constabulary, during years 3 and four and later v or more years. All unilateral coefficients are statistically significant, with the exception of column (4) after v years or more. State trends are jointly meaning, and the adjusted R two increases from specification (1) to (4).

According to estimates in columns (2) to (4), the introduction of unilateral reforms increases divorce rates in the curt run from 0.21 to 0.28 annual divorces per thousand people. Over years 3 and four, the upshot increases in size for specifications (2) and (iii) and remains very similar for specification (four). Finally, 5 or more than years after the reform, the impact is still positive but starts to diminish, affecting divorces rates by 0.29 and 0.25 annual divorces per 1000 people, according to specifications (two) and (3), respectively. Tests accept been performed on the equality of the three coefficients of unilateral in each specification, rejecting the hypothesis that they are similar for specifications (3) and (4) at standard confidence levels, supporting the strategy followed in this department. A potential caption of the higher effect of the change in law in years 3 and 4, rather than during the first 2 years, is that initially, the changes in the divorce government are not widely known by the population, taking time for the information to be disseminated. Time is as well necessary for divorce to get more acceptable, and people gradually become more open to ending a marriage that no longer works as more than couples go separated. In addition, the process of filing for divorce under unlike rules can exist hard to sympathise at the beginning, delaying the conclusion. The positive but smaller size of the effect on divorce rates of no-mistake divorce afterwards 5 or more years indicates that although the dynamic response to the policy shock persists in the medium term, the effect of the law change over the following years might gradually be reduced as an aligning to a temporary boom of inefficient marriages breaking up immediately after the reform. It is important to highlight that comparing the static and dynamic estimates for unilateral in Tables 2 and 4, the coefficients do non vary much and remain very similar, confirming a shut relationship between changes in divorce legislation and divorce rates, regardless of the approach that is followed.

Control variables

To explicitly business relationship for observed heterogeneity, v variables are included in the assay: education, Footnote 12 female labor forcefulness participation, fertility rates, Footnote xiii gdp (GDP) and unemployment. The inclusion of these controls aims to reassess the affect of unilateral legislation on divorce rates when some country-level variables are added to the model. The results for the static and dynamic specifications, reported in Tables 9 and 10 in Appendix, are virtually identical to those presented in Sects. 5.1 and v.two for the effect of divorce legislation, validating the inclusion of state-stock-still furnishings and trends in the analysis in order to capture the effect of other factors that affect divorce rates.

In terms of the new variables added to the model, simply unemployment turned out to be meaning in most specifications. However, contrary to what the literature suggests (Becker et al. 1977), an increment in unemployment leads to an unexpected reduction in divorce rates in Mexico. An caption for this is that divorce itself costs money, so the inability to afford a divorce for individuals facing unemployment, and the fact that it costs more for a couple to live separately than together, may be preventing married couples in developing countries from filing for divorce when unemployment rates are higher. Another possible explanation is that spousal relationship might exist seen equally some sort of informal insurance against unemployment, becoming more than valuable when unemployment is high.

Unweighted specifications and changes in the functional class

All of the previous estimations have been performed using weighted least squares (WLS) to correct for the presence of heteroscedasticity generated by the utilise of state-level divorce rates rather than private information on divorce decisions. However, information technology has been argued that estimations under WLS and ordinary least squares (OLS) should exist like if the unobserved heterogeneity is adequately addressed (Kim and Oka 2014). Following Droes and Lamoen (2010), the transformed model using analytical weights is:

$$\brainstorm{aligned} {\text{Divorce Rate}}_{s,t} \sqrt {{\text{pop}}_{s,t} } = & \beta {\text{Unilateral}}_{southward,t} \sqrt {{\text{pop}}_{s,t} } \\ & + \mathop \sum \limits_{s} {\text{Country fixed effects}}_{s} \sqrt {{\text{pop}}_{s,t} } + \mathop \sum \limits_{y} {\text{Twelvemonth stock-still furnishings}}_{y} \sqrt {{\text{pop}}_{s,t} } \\ & + \mathop \sum \limits_{s} {\text{Land}}_{south} *{\text{Time}}_{t} \sqrt {{\text{pop}}_{south,t} } + \mathop \sum \limits_{s} {\text{Country}}_{s} *{\text{Time}}_{t}^{ii} \sqrt {{\text{pop}}_{s,t} } + \varepsilon_{south,t} \sqrt {{\text{pop}}_{south,t} } \\ \cease{aligned}$$

(iii)

where \({\text{pop}}\) is the state population in thousands. It is observed that the coefficient for unilateral divorce remains equal after the transformation. Lee and Solon (2011), and Droes and Lamoen (2010), using Wolfers (2006) and Friedberg'south (1998) data, estimate the effect of unilateral divorce using OLS. In addition, Lee and Solon (2011) perform estimations using the logarithm of the divorce rate, claiming that this is besides a valid functional specification. The results for the USA propose that the change in police has no effect on divorce rates, neither when OLS regressions are estimated nor when the dependent variable in the analysis is the divorce charge per unit in log, casting doubt on the true result of unilateral legislation in that country.

Weighting by population to correct for heteroscedasticity in gild to obtain efficient estimators relies on the stiff assumption of homoscedastic and independent error terms for individuals within the state. However, if individual error terms share a common land-level fault component, the unweighted state-average mistake terms are closely homoscedastic. In this scenario, the employ of WLS would exacerbate whatsoever existing heteroscedasticity, and OLS estimation would be more efficient than WLS. Large discrepancies betwixt the results obtained using WLS and OLS might exist an indication of functional form or model misspecification. Therefore, estimations based on OLS without weighting are also important to perform and report. Too, given the nature of the dependent variable used within this context, an always positive divorce rate, it is possible to consider different functional specifications, such as the logarithm of divorce rates. Typically, the results based on changes in functional class assumptions are expected not to be extremely sensitive to these modifications, supporting previous findings and providing compelling testify for the main conclusions in the assay.

To decide if the results obtained for Mexico are still valid following these approaches, Tables 11 and 12 in Appendix written report the OLS estimates, and Tables 13, 14, xv and 16 present the estimations when using the log of the divorce rate. As discussed by Lee and Solon (2011), the OLS coefficients obtained are smaller than the WLS estimates, given that WLS places more weight on those states that are more populated, and given that unilateral divorce has larger effects on these states. Yet, in contrast to the results for the USA, the coefficients obtained for unilateral legislation go on to be positive and statistically significant in practically all specifications. These findings provide compelling evidence that unilateral divorce has an effect on the divorce rates in Mexico, regardless of the estimation methods or the functional grade assumed.

Conclusion

This report evaluates the event of unilateral legislation on divorce rates in United mexican states. A large number of economical research studies take analyzed the relationship between these two variables by using dissimilar methodologies. Findings for the U.s. and Europe point that no-fault divorce has an undeniable office in explaining the increases in divorce rates. However, there are no previous studies analyzing the consequences of unilateral legislation on divorce rates in Latin America, possibly because divorce on no grounds is a recently enacted legislation in the region.

Post-obit a difference-in-differences arroyo, two models are developed using panel state-level information. The preferred static specification indicates that the shift toward divorce on no grounds raises the divorce charge per unit by 0.30 annual divorces per grand people and accounts for the 26.4% increase in the total number of divorces in the adopting states during the period 2009–2015. In order to distinguish between the immediate furnishings of the policy stupor and the affect that it has in the medium run, a dynamic model is also estimated. The preferred dynamic specification suggests that during the first two years after the change in law, the divorce rate increases by 0.27 almanac divorces per grand people, only in the tertiary and fourth years, the event is even larger with 0.36 almanac divorces per yard people. Five or more years after the reform, although the effect is still positive and meaning, a smaller upshot of 0.25 divorces per 1000 population per yr is observed. These results may be an indication of an inverted U-shaped relationship between the divorce rates and changes in divorce law over time in Mexico. In addition, they illustrate the importance of promoting information about the reform.

The positive effect of unilateral legislation on divorce rates rejects the empirical validity of the Becker–Coase theorem for United mexican states, at least in the short and medium term. Moreover, since divorce on no grounds has been adopted gradually in the land by unlike states, the rise trend in divorce rates is expected to continue over the following years.

The findings of this research are relevant for the country, peculiarly during this transition period, when a total of 18 states have already changed their divorce legislation toward no-mistake divorce, only there are withal 14 states remaining that may potentially adopt unilateral divorce. Start, they explicate the higher divorce rates observed in Mexico, especially over the last few years. Moreover, they shed light on the effectiveness of these types of policies, allowing individuals who no longer wish to remain in a marriage to end information technology in a less costly, time-consuming and strenuous manner. However, they also pose the question of whether relaxing divorce laws encourages couples to surrender more than easily on their marriages, especially younger people, and undermines the institution of marriage. In terms of boosted policy implications typically associated with other countries that allow unilateral divorce, at that place is a lack of studies in Mexico and Latin America. More research on the region is needed to understand the effects of changes in divorce legislation on domestic violence, female labor force participation, fertility rates, children outcomes and income inequality, amongst others. Since unilateral legislation has proved to be an effective tool for modifying family structures in Mexico, it is of import for policy makers to be aware of the consequences of the shift toward unilateral divorce in club to deliver changes in divorce laws more effectively.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (and its Additional files 1, 2, iii, 4, 5, 6 and seven).

Notes

-

No-fault divorce is a petition by either political party of the matrimony that does not crave the petitioner to provide evidence that the defendant has breached the marital contract. However, the terms "unilateral divorce" and "no-fault divorce" are used synonymously throughout this newspaper because in the instance of United mexican states, ane implies the other.

-

The declaration of unconstitutionality means that when a married individual goes to a federal judge and asks for an injunction confronting the state that denies the unilateral divorce, the approximate must grant it.

-

Jurisprudential thesis ways that this decision does non straight repeal whatever law prohibiting unilateral divorce.

-

For simplification purposes, Mexico City will be referred to equally a land in the rest of the document.

-

National Surveys on the Dynamics of Household Relationships (ENDIREH), 2006, 2011 and 2016.

-

Usually, both Northward and T are larger than 30.

-

This is different from Friedberg and Wolfers, given the need for a balanced panel in interactive stock-still effects.

-

Information technology has been argued that the divorce charge per unit should be measured using the number of marriages instead of the population. However, since the data on marriages is not readily available, this definition of the divorce charge per unit has been usually accustomed.

-

Following Hsiao (2014), when using standard errors amassed past the cross-sectional variable, the number of groups should be large. This supports the utilise of WLS every bit a more than appropriate strategy, given that there are merely 32 states in the analysis.

-

Baja California Sur, Mexico City, Michoacan, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas are in this situation.

-

As Table 1 indicates, during the period from 2008 to 2016, 18 states changed their divorce law. However, divorce data are not yet available for 2016, so the 6 states that moved toward unilateral divorce in 2022 (Baja California Sur, Colima, Morelos, Nuevo Leon, Puebla and Tlaxcala) and the two states that shifted to information technology in the second half of 2022 (Michoacan and Tamaulipas) are not included as handling states in the assay.

-

Boilerplate grade of schooling.

-

Total number of live births per chiliad females of childbearing age between the ages of 15 and 49 years.

References

-

Allen DW (1992) Marriage and divorce: comment. Am Econ Rev 82:679–685

-

Allen DW (1998) No-fault divorce in Canada: its cause and effect. J Econ Behav Organ 37:129–149

-

Bai J (2009) Panel information models with interactive fixed effects. Econometrica 77:1229–1279

-

Becker GS (1991) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press Enlarged version, Cambridge

-

Becker GS, Landes EM, Michael RT (1977) An economic analysis of marital instability. J Polit Econ 85:1141–1187

-

Caceres-Delpiano J, Giolito Due east (2012) The touch of unilateral divorce on criminal offense. J Labor Econ 30:215–248

-

Chiappori PA, Mt Iyigun, Weiss Y (2015) The Becker–Coase theorem reconsidered. J Demogr Econ 81:157–177

-

Clark SJ (1999) Law, holding, and marital dissolution. Econ J 109:C41–C54

-

Coase RH (1960) The trouble of social price. J Constabulary Econ 56:837–877

-

Conley TG, Taber CR (2011) Inference with divergence in differences with a small number of policy changes. Rev Econ Stat 93:113–125

-

Donald SG, Lang 1000 (2007) Inference with divergence in differences and other panel data. Rev Econ Stat 89:221–233

-

Droes M, Lamoen R (2010) Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results: comment. Utrecht School of Economics, Discussion Newspaper Serial ten–xi

-

Ferman B, Pinto C (2018) Inference in differences in differences with few treated groups and heteroscedasticity. Rev Econ Stat. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00759 (forthcoming)

-

Friedberg 50 (1998) Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Bear witness from console information. Am Econ Rev 88:608–627

-

Gonzalez L, Viitanen TK (2009) The event of divorce laws on divorce rates in Europe. Eur Econ Rev 53:127–138

-

Gruber J (2004) Is making divorce easier bad for children? The long-run implications of unilateral divorce. J Labor Econ 22:799–833

-

Hsiao C (2014) Analysis of panel information, 3rd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

-

Kim D, Oka T (2014) Divorce police reforms and divorce rates in the Usa: an interactive fixed-effects approach. J Appl Econom 29:231–245

-

Lee J, Solon G (2011) The fragility of estimated furnishings of unilateral divorce laws on divorce rates. Be J Econ Anal Poli 11, Article 49

-

Mechoulan Due south (2005) Economic theory's stance on no-fault divorce. Rev Econ Househ three:337–359

-

Moon HR, Weidner M (2015) Linear regression for console with unknown number of factors every bit interactive stock-still effects. Econometrica 83:1543–1579

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2017) Building an inclusive Mexico: policies and good governance for gender equality. OECD Publishing, Paris

-

Peters HE (1986) Marriage and divorce: informational constraints and private contracting. Am Econ Rev 76:437–454

-

Stevenson B (2007) The bear upon of divorce laws on marriage-specific majuscule. J Labor Econ 25:75–94

-

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2006) Bargaining in the shadow of the law: divorce laws and family distress. Q J Econ 121:267–288

-

Wolfers J (2006) Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. Am Econ Rev 96:1802–1820

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge Karen Mumford, Thomas Cornelissen, Emma Tominey and participants at diverse seminars, for helpful comments as well as the fiscal support provided by the Mexican Council of Scientific discipline and Technology (CONACYT). I especially thank an bearding referee for precise comments and suggestions.

Funding

Mexican National Council for Scientific discipline and Technology (CONACYT).

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

This is the showtime study to clarify the implications of unilateral legislation on divorce rates not only in Mexico simply in a Latin American country, and helps to empathize better the increasing number of divorces in recent years. In addition, it proves that these types of changes in the legislation are powerful tools that immediately alter outcomes inside families, regardless of the social and cultural groundwork that distinguish the Latin American region. The author read and canonical the last manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary data

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. i, 2 and Tables five, 6, vii, 8, ix, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this article

Aguirre, E. Do changes in divorce legislation have an impact on divorce rates? The case of unilateral divorce in United mexican states. Lat Am Econ Rev 28, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40503-019-0071-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40503-019-0071-seven

Keywords

- Divorce rates

- Unilateral divorce

- Difference-in-differences

- Mexico

JEL Nomenclature

- C29

- J12

- J18

Source: https://latinaer.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40503-019-0071-7

0 Response to "No Fault Divorce Impact on Divorce Statistics Families"

Post a Comment